An Introduction to Charles Pfaff and His Cellar

On May 10, 1890, approximately three weeks after the death of Charles Ignatius Pfaff, the Omaha Daily World-Herald in Omaha, Nebraska, printed what is, perhaps, the most unusual obituary known to date for the New York restaurateur. The writer of the piece referred to Pfaff as “the Gannymede of Bohemia” in part because he was the bearer of countless cups of wine and mugs of lager beer for his literary and artistic clientele. But the most striking aspects of the obituary are the writer’s understated tone and his succinct assessment of Pfaff’s lifelong career in the restaurant and saloon business:

Pfaff is dead. He was not a bank president or a railway king and he had never been in politics, so the newspapers did not say much about his death. He was just a plain German who kept a saloon in a Broadway basement for over a quarter of a century. That is not much to become famous for, but it was all he could do and he did it well.1While it is true that Pfaff was never a prominent financier or a politician, the World-Herald obituary pays the restaurateur a somewhat backhanded compliment when it acknowledges the significance of the eating and drinking establishments in New York City that Pfaff presided over throughout his life. As it will soon become evident, this “plain German” was, in fact, a savvy saloonkeeper and businessman, and he was well respected by the many customers who visited one or more of his places.2 Those who were familiar with him described him as a “rotund” man with “short, bristling hair” and “a large geniality of manner.” His friends and customers—many of whom contributed to a variety of newspapers and literary journals—ensured that Pfaff was known throughout the city and beyond as a “patron of letters” and a friend of “penniless scribbler[s]” because he “dispens[ed] vast quantities of beer and cheese” to the city’s professionals, French and German immigrants, soldiers, and laborers for nearly thirty years.3

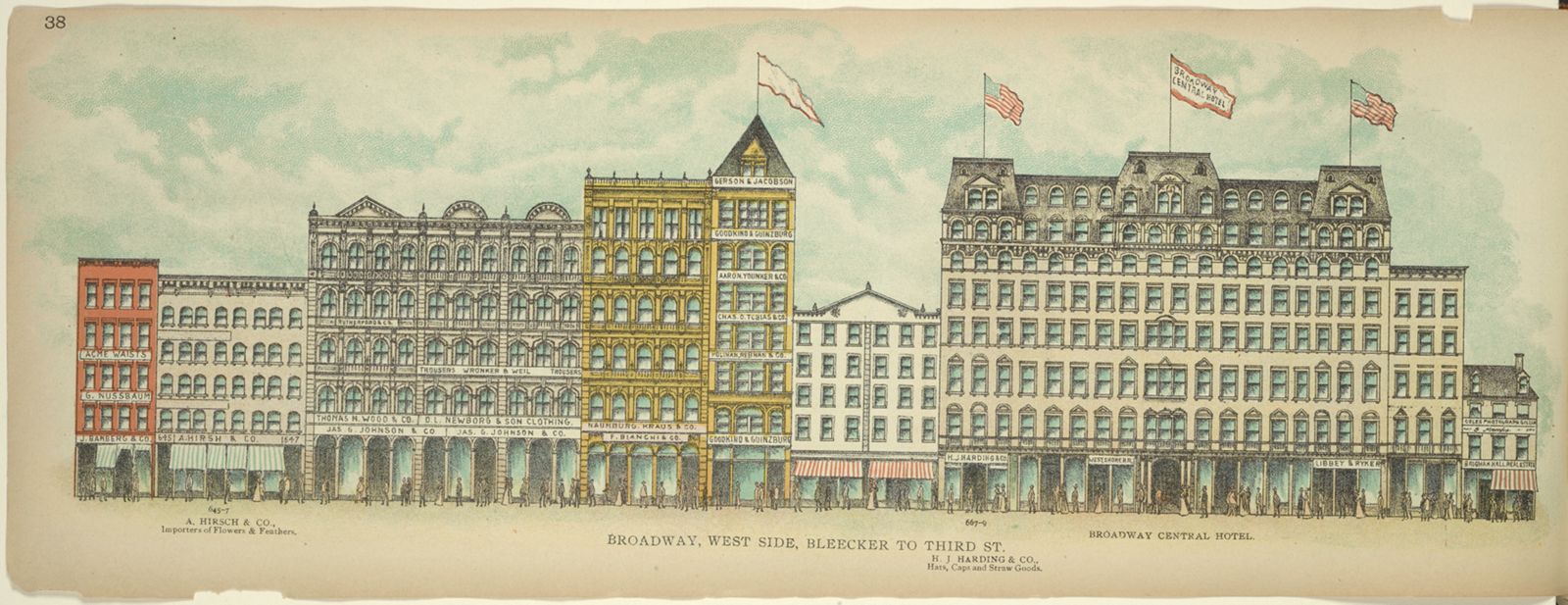

In 1859, Charles Pfaff opened his most famous establishment—a wine and lager beer cellar located at 647 Broadway. Over the next two years, this address became a resort for a group of writers, artists, journalists, illustrators, and actors. These men and women are now regarded as the first group of “self-conscious and self-proclaimed” American Bohemians.4 Dubbed “Pfaff’s” by these regular customers—who came to be known as Pfaffians—the beer cellar earned a reputation as “the trysting-place of the most careless, witty, and jovial spirits of New York” and as a basement haunt where “food and drink were cheap and good” and “habits of dress, speech, and thought, unconventional.”5

For the American Bohemians, Pfaff’s cellar was not only their preferred meeting place, but it also became a significant site for their literary and artistic productions. Here, they composed and discussed their contributions to the New-York Saturday Press, a “saucy, clever, independent literary weekly,” edited by Henry Clapp, Jr., who was known as the King of Bohemia among the Pfaffians.6 America’s poet Walt Whitman received an incredible amount of attention—both positive and negative—in the Press since the paper published “no fewer than 46 items” that were either about or authored by the poet during the first year of its run.7 Whitman, one of the few members of the Bohemian group who remains well known today, even composed his “Calamus #29” in the late 1850s, as well as a seemingly unfinished poem "The Two Vaults" in the early 1860s, while he was frequenting Pfaff’s cellar. The American Bohemians’ articles and illustrations also appeared in Vanity Fair (1859-1863), a “humorous and satirical” weekly edited by William Allan Stephens that, according to Frank Luther Mott, was “born in Pfaff’s cellar, Bohemian gathering place of the wits of the fifties.”8 Julius Chambers, writing for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1906, explained that American literature owed a considerable debt to Clapp and his fellow Bohemians because they “blazed the trail across the murky, unsurveyed heather of American Literary endeavor” as they sat at Pfaff’s tables with their coffee and lager beer.9

But Pfaff’s restaurant and lager beer saloon—with its strong ties to American literary history and nineteenth-century periodical culture—was neither the beginning nor the end of Charles Pfaff’s reign as the proprietor of eating and drinking houses in the city. Although any history of Pfaff’s is inextricably tied up with the development of the first American Bohemia in antebellum New York, the story of Pfaff’s saloons and restaurants began well before

This page has paths:

- “GO TO PFAFF’S!” Audrey Clancy