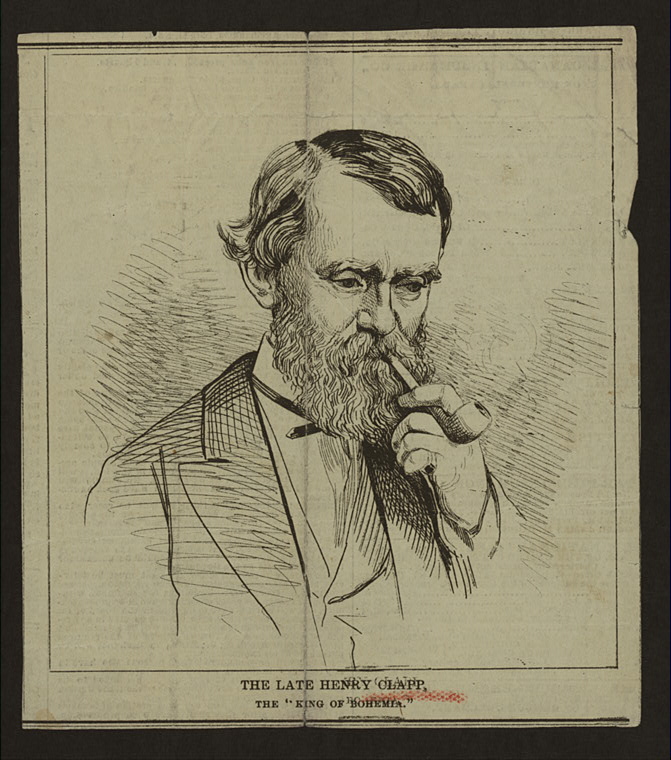

Henry Clapp, Jr. and the Discovery of Pfaff’s

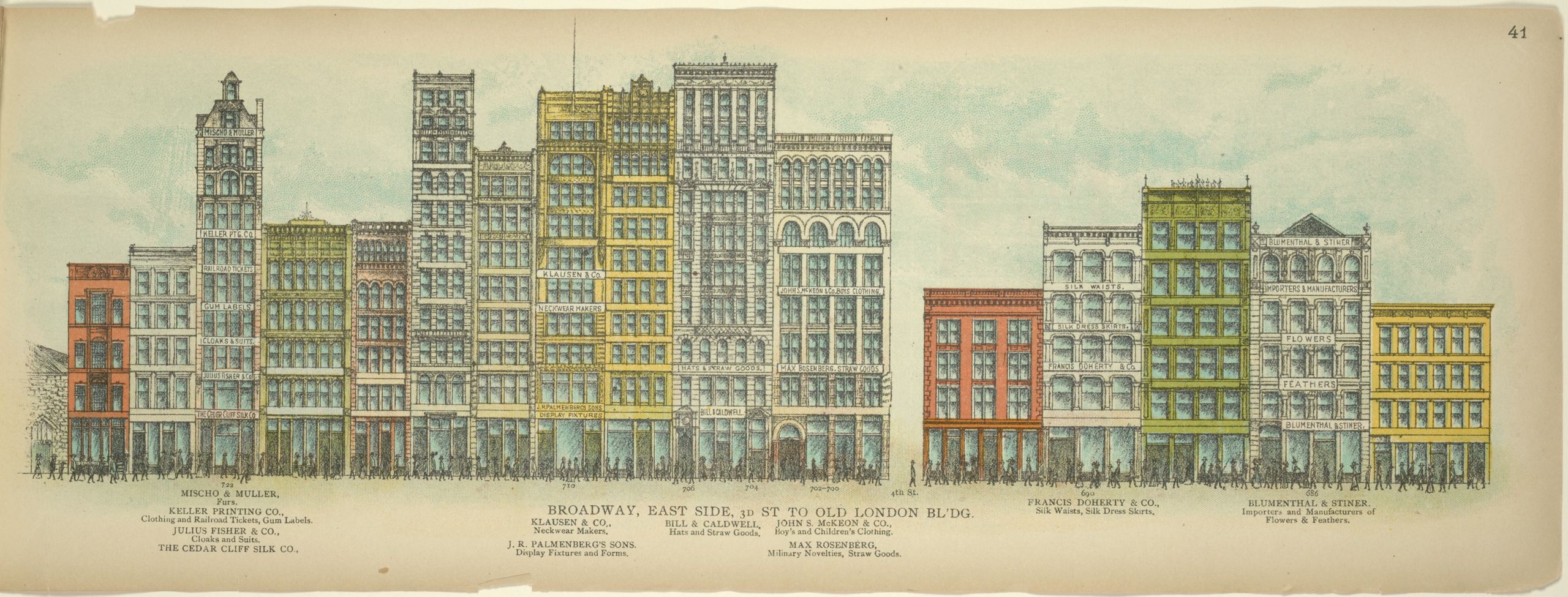

Because the American Bohemians’ own accounts of their early days at Pfaff’s differ from that published in The Night Side of New York, it is difficult to determine precisely when and where they first came to an eating and drinking house owned by Charles Pfaff. Nevertheless, I can shed some light on their early years at Pfaff’s establishments. If Clapp and the men and women who would form the American Bohemian coterie began going to Pfaff’s in 1856, it remains uncertain as to whether they went to the eating house at 685 Broadway or to the address of an even earlier and as yet unknown establishment. What is certain is that in 1856, these individuals could not have discovered the Pfaff’s at 647 Broadway, which they frequented just before the beginning of the Civil War, because the saloon did not yet exist and, indeed, Pfaff would not open a saloon at this address until three years later, in 1859, as a removal notice, published in the New York Herald confirms.4 It is also worth clarifying here that the restaurant and saloon at No. 653 Broadway opened at an even later date, in approximately 1864; thus, the Bohemians could not have gone to that address until the last years of the Civil War. In short, if the Bohemians discovered Pfaff’s in 1859, they could have gone to the 685 establishment until approximately the end of March; afterwards, it would have been necessary for them to accompany Pfaff as he moved into his new saloon at 647 Broadway.

It may have been in 1856, then, approximately three years before Walt Whitman met the American Bohemians at Pfaff’s, that Clapp—the leader or the “King” of that talented group—decided that an early version of Pfaff’s was an ideal location for men and women interested in practicing la vie Bohème in New York. It may have also been as late as 1859, just months before Clapp’s coterie would make 647 Broadway famous, that he chose this particular address as the future home of American Bohemia. In either case, Clapp’s own travels in Europe no doubt influenced the place he selected and the men and women that he helped to bring together in a basement beer cellar in antebellum New York. When Clapp was in his early-thirties, he had lived and traveled abroad, spending three years in London before moving to Paris in 1849.5 In Europe, Clapp, “the product of a New England reform tradition that almost always denounced sex, alcohol, tobacco, and coffee as physically harmful and spiritually sinful,” started smoking, consumed beer and other alcoholic beverages, and drank coffee with milk and sugar.6 In addition to London, which Clapp referred to fondly as a “dear old fogie metropolis” that he knew “by heart,” he visited Oxford, Cambridge, Windsor, and Brighton.7 Yet what he recalled best were not England’s cities, but rather, its places of entertainment. As Clapp put it in an article for the Saturday Press, “I supped at Evan’s, bowled at Kilpack’s, heard “Sam Hall” at the Cider Cellars, [and] played chess at the Cigar Divan.”8

After leaving England, Clapp went to Paris, and while he was there, he frequented a Coffee Concert located about ten minutes’ walk from his room at the Hôtel Corneille.9 Although Clapp estimated there were at least fifty such coffee concerts in Paris, he felt that only this one—his “favorite place of amusement”—was worth describing in such vivid detail to the Press’s readership. According to Clapp, the establishment was “a queer multiangular-shaped hall, abounding in mysterious alcoves and corners, and capable of holding from four to five hundred persons.10 The room itself contained “about a hundred deal-wood tables,” each of which could seat about four persons. Each patron placed his or her order and then settled in to watch the singers and performers on the Concert Room’s richly decorated stage. Clapp enjoyed the performances and the place’s conversational atmosphere, and the Coffee Concert became part of the “realm of Bohemians,” where Clapp and crowds of young students (among others) gathered to smoke, drink coffee, and talk.11

When Clapp returned to New York in the winter of 1853-54, he longed for hangouts like the Coffee Concert and the English cider cellars he had visited in Europe, or like those establishments with atmospheres conducive to conversation that the writer Henri Mürger had then only recently described in his book Scènes de la Vie de Bohème (1851).12 Some time later, as early as 1856 or as late as 1859, Clapp may have stumbled upon the perfect place to found an American Bohemia: Pfaff’s cellar. One account suggests that Clapp discovered Pfaff’s when he was living in Broadway, near Bleecker. At the time, he was searching the nearby establishments for an inexpensive cup of coffee. By chance, he descended into Pfaff’s cellar, where he found coffee as well as food and lager bier at cheap prices.13 As previously mentioned, Lause and Wilson state that both Clapp and Fitz-James O’Brien found the beer cellar and subsequently recommended it to their friends because of the taste and the quality of Pfaff’s beer and/or his other drink offerings, particularly his coffee.14 In an article for Harper’s Magazine, George Parsons Lathrop maintains that three contributors to late 1850s periodicals had planned to meet to discuss ideas for a new weekly paper, perhaps, the Saturday Press, the newspaper that Clapp edited and to which several of the American Bohemians made significant contributions throughout its brief run. When it began to snow, the men decided to take cover in a “dingy resort below the level of the sidewalk, where beer was sold in a room screened off from the domestic department by a calico curtain. This was Pfaff’s and thus arose the ‘Pfaff group.’”15

Still another account credits Fitz-James O’Brien with introducing the American Bohemian group to Pfaff’s. In the Brooklyn Standard Union, Amos Cummings details how O’Brien went to Pfaff’s and ordered coffee even though “he had been drinking cognac, and to one who has crucified his appetite with cognac the best coffee tastes insipid.” O’Brien sampled his steaming beverage, then he “cursed his coffee and declared that he would never again visit Pfaff’s, but he did, and the next day, when he quaffed the Teuton’s coffee, it addressed itself so strongly to his palled palate that he was delighted.” Indeed, O’Brien was so pleased with Pfaff’s coffee that he wrote an article about the cellar for a New York periodical and, as a result, “the honest German suddenly found himself famous.”16

But regardless of whether the discovery of Pfaff’s came as a result of Clapp’s thirst for coffee, an unexpected snow shower, or a combination of O’Brien’s taste for cognac and his journalistic skills, the establishment, with its dark vault, selection of European spirits, and French and German fare, almost certainly reminded Clapp of the years he spent socializing with other writers and artists in the Bohemian cafes and underground rathskellars of Paris and London. It was this European cultural and social scene that Clapp aimed to recreate on American soil—in the presence of and in an establishment owned by Charles Pfaff. After all, it was Clapp’s “effort and influence that made Pfaff’s into something like a Bohemian restaurant of the Latin Quarter.”17

When Henry Clapp and/or Fitz-James O’Brien praised Pfaff’s drinks in the pages of the Saturday Press and among their acquaintances, other writers, artists, and actors joined them at the cellar:

Then the old cellar was found to be inadequate to the increasing custom of the place, and for years, Pfaff located himself in a larger one, on Broadway, near Bleecker street. This cave became quite a celebrated resort for artists, critics, actors, and the literary brotherhood at large, having, besides, its large entourage of German, French and other foreign custom, which gave a somewhat European character to the place.18

This page has paths:

- “GO TO PFAFF’S!” Audrey Clancy