The Loss of 9 W. 24th Street and the Death of Charles Pfaff

Charles Pfaff remained in the restaurant business until April 1887, three years before his death.1 He retired only when he lost his lease on the space at 9 W 24th Street. Amos Cummings, writing for the Brooklyn Standard Union, reported on Pfaff’s reaction to the loss of his restaurant. Cummings visited the “veteran restauranteur [sic]” and described a sobering scene during which Pfaff, now a “stocky man with a full gray beard, trimmed in the Prince of Wales style” came to his meeting with Cummings and immediately “threw down his hat with an air of despair” and “began to talk about the gay days of the past.”2 Pfaff had tears in his eyes as he recalled better days, namely the years when the Bohemians patronized his place. Pfaff was clearly heartbroken over his loss, but he almost certainly felt anger and frustration over the incident as well. He explained that in April 1887, Mrs. Benson, who owned the space that he rented for his business, came to Pfaff and “demanded an advance of $500 per year on his rent, making it $4,500 [illegible].” Pfaff was unable to pay the additional money, and, therefore, the contents of his place were to be sold at auction.3

On Monday, April 25, 1887, a notice appeared in the New York Herald by Richard Walters’ Sons Auctioneers, announcing a sale that very day at 10:30AM at “Pfaff’s Hotel”; the items listed for sale at the auction included, restaurant supplies such as a “Bar and Back Bar, Tables, Chairs, Glassware . . . Table linen, Ranges, Kitchen Ware” along with furnishings, presumably from the hotel rooms, including “Wardrobes, Bedding, Tables, Parlor furniture, Brussels Carpets.”4 In their conversation, Pfaff revealed to Cummings that he believed the reason for the sudden demand for additional rent and the subsequent auction was that F. I. Stokes [illegible] was anxious to obtain the property Pfaff leased in order to utilize it as an annex to the nearby Hoffman House.5 Pfaff’s suspicions that the Hoffman House was interested in the 9 West 24th Street property do not, in retrospect, appear unfounded. In September 1877, a notice appeared in The New York Herald promising that the “Parlor Floor” inside the establishment—likely the same floor Pfaff himself had previously rented to social clubs—was again available as were the living quarters on the third floor; application could be made for either “at the office of the Hoffman House.”6 In part, as a result of this successful bid to expand the Hoffman House Hotel, Pfaff, who had long operated a series of largely successful cellars and restaurants lost nearly everything and believed, seemingly with good cause, that he had deliberately been put out of business.

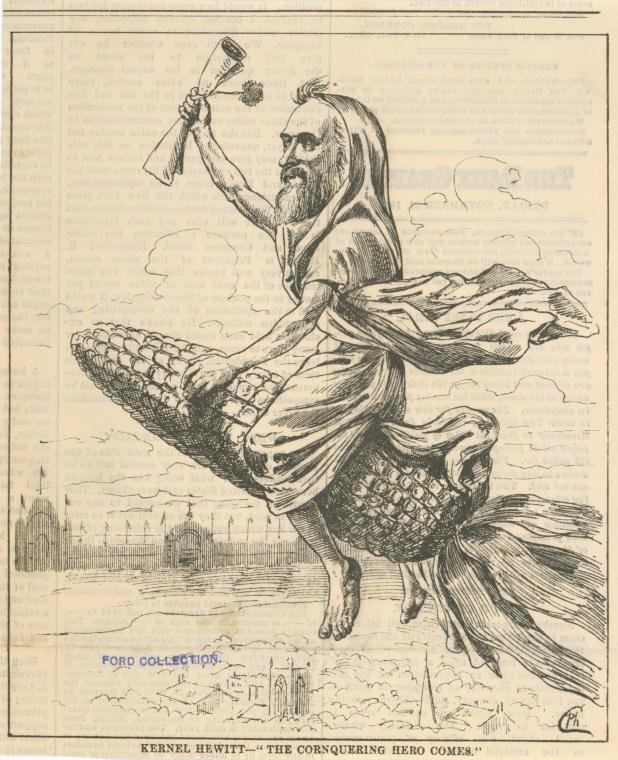

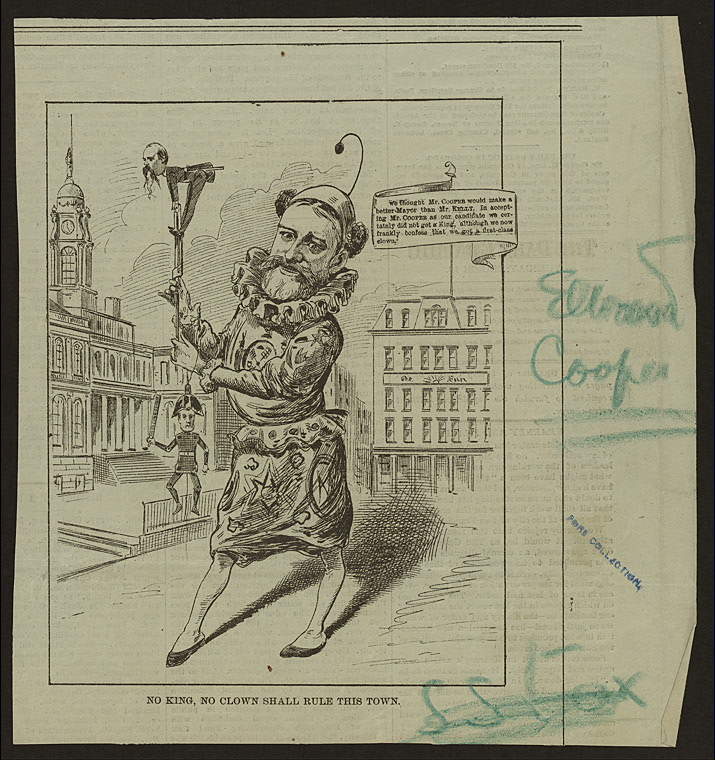

Following the sale of the furnishings from Pfaff’s restaurant and hotel, all that remained of the famous location was two barrels “of ashes and rubbish upon the sidewalk.”7 In late June 1887, nearly three months after the auction, Abram Hewitt—then Mayor of New York—and former mayor Edward Cooper were walking toward the New Amsterdam club when they came across “two barrels filled with debris from Pfaff’s once-famous hostelry, which ha[d] migrated from that vicinity” sitting on the sidewalk. Mayor Hewitt and Cooper moved the barrels, pulling them “toward the depressed area of Pfaff’s.” The remnants of Pfaff’s were thus secured against a wall, and the two men proceeded to the club “with the consciousness of a duty well done.” Some three years later, the last trace of Pfaff’s hotel seems to have been removed. James Ford, presumably on a walk down W. 24th Street, noticed that sometime after the proprietor’s death, the “gilded signboard” that had directed customers to Pfaff’s had been taken down, and the place was long since closed.8

Although Charles Pfaff was devastated by the loss of his business, it is also true that the earlier fame and fortune that had been associated with his Broadway locations had not followed him to 9 W. 24th Street.9 Whereas Pfaff had many customers and earned “hundreds of dollars in daily custom” on Broadway, he actually lost money at his last hotel and restaurant.10 After his death, The New York Times emphasized Pfaff’s financial woes and even went so far as to imply that it was Pfaff’s generosity, the fact that he “lent and spent it [money] as freely as he made it,” that may have contributed to his financial difficulties and, by extension, his inability to pay for the increase in rent. Also, by 1887, since many of the Bohemian crowd had already died, “he found it next to impossible to call in his loans” even though he had given these men and women credit or even supported them in their last years.11 These financial circumstances may have also prohibited him from leasing “cheaper quarters farther uptown and open[ing] a new resort” after he lost his hotel.12 The stress of these financial circumstances was, no doubt, a terrible burden for Pfaff to bear. At that time, his son, Charles, Jr., may have been helping his father with the hotel, or he may have already secured a position as a clerk. In either case, even if Pfaff, Jr. was earning a clerk’s salary at the time, it was not likely that he would have had the financial means to ensure that the family could continue in the hotel business. Charles Pfaff Sr.’s friends were even convinced that the extended financial worries and the ultimate loss of his restaurant and hotel “had much to do with hastening his death.”13

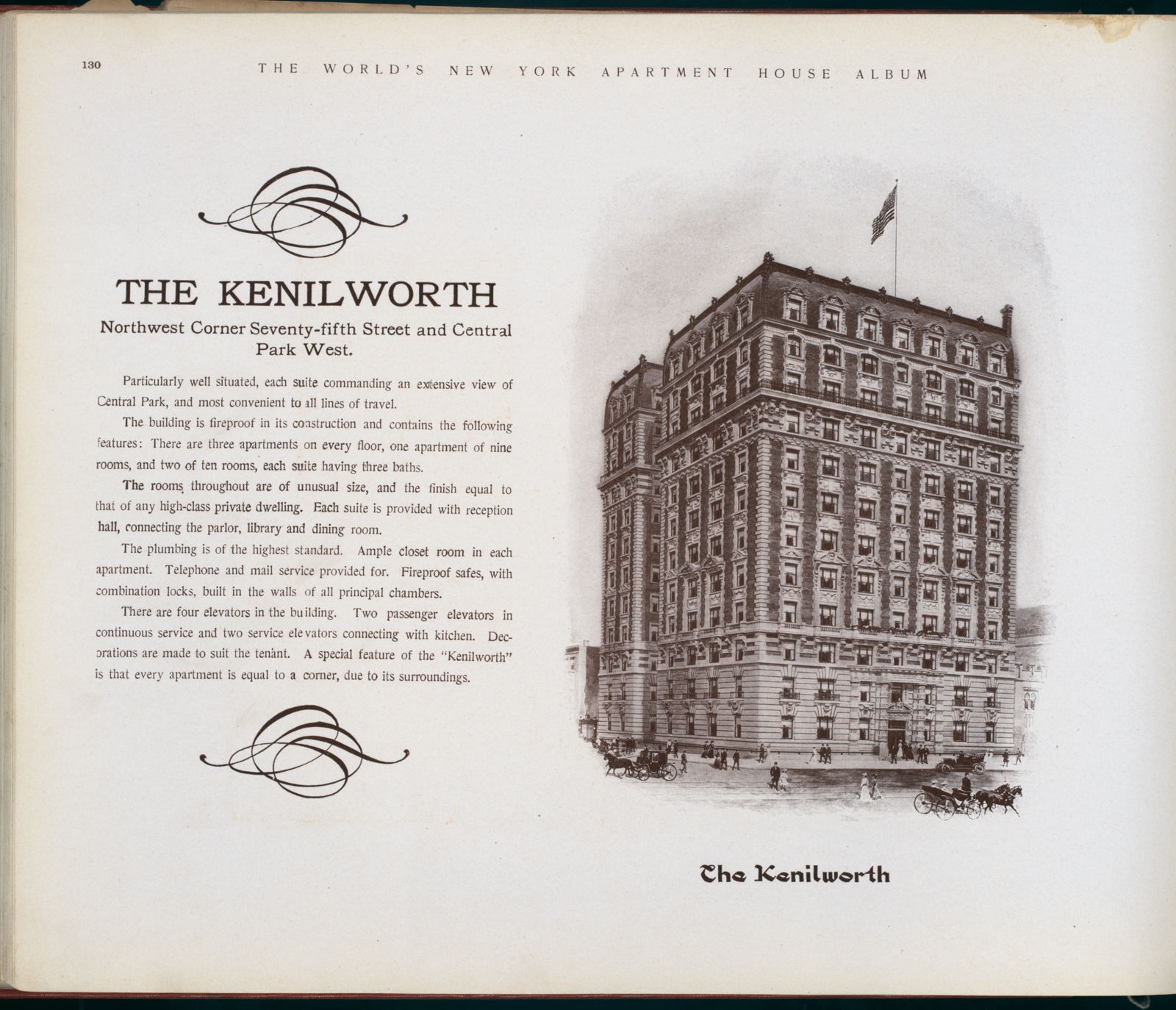

Charles Pfaff spent the last three years of his life in retirement. “Papa Pfaff,” as his customers liked to call him, died on Wednesday, April 23, 1890 of acute gastritis or “gastric hemorrhage in his 72nd year.”14 Pfaff died at home, and he was, at that time, residing at the

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that several newspapers did print obituaries for the once-famed proprietor.18 An examination of the extant obituaries for Pfaff, however, suggests that the World-Herald writer was correct to point out that, following Pfaff’s death, few newspapers provided extensive biographical information about Pfaff or even related the circumstances surrounding his retirement from the restaurant business. The Cambridge Tribune reported in its “Library Chat” column, “That an obscure restaurant keeper died last week in New York does not seem at first thought a matter for library mention.” The writer continues, “That this obscure feeder of the people was Charles Pfaff, who once kept the only Bohemian restaurant in that city, will not rouse sentimental memories in the minds of many, if any, of our readers.”19 Yet, the writer must have believed that a brief history of Henry Clapp and Ada Clare would strike a chord with the paper’s readers since they feature more prominently in the article about Pfaff’s death than the proprietor himself. Like The Cambridge Tribune, several other newspaper writers chose to focus on the literary and artistic patrons who frequented Pfaff’s once thriving establishments, while providing a broad, retrospective view of the proprietor’s career as a whole. In short, although newspaper readers were at least able to learn about Pfaff’s final illness and his death, there was a clear lack of information about his life, and there is only one known obituary that mentions the fact that the proprietor was survived by a son, Charles Pfaff, Jr.20

Charles, Jr., who was likely still living in New York when his father passed away, may have been one of the restaurateur’s few surviving family members; he is certainly the only direct descendent to be mentioned by name in an obituary for Pfaff, Sr.21 The former restaurant and saloon owner’s funeral was held on Saturday, April 26, 1890. The conductor of the funeral services was the Reverend John Godson from the Jane Street Methodist Episcopal Church.”22 The only people who attended the funeral, presumably according to Pfaff’s wishes, were his son, other “members of Mr. Pfaff’s family and their most intimate friends.”23 None of the individuals in attendance are named in The New York Times. Pfaff was buried in Green-wood cemetery on the same day, and his burial record and seemingly his death certificate are filed under the name of “IGNATIUS PFAFF.” There was no will, so Charles Jr., had to write to obtain a letter of administration in order to take over his father’s affairs, which, according to New York City probate records was granted to the younger Pfaff and recorded on May 21, 1890.24 After this date, Charles Pfaff, Jr., then approximately thirty-three years old, presumably settled any of his father’s business affairs and went on to establish himself in a series of careers in New York.

This page has paths:

- “GO TO PFAFF’S!” Audrey Clancy