Pfaff’s “New Wein and Lager Bier Saloon and Restauration”

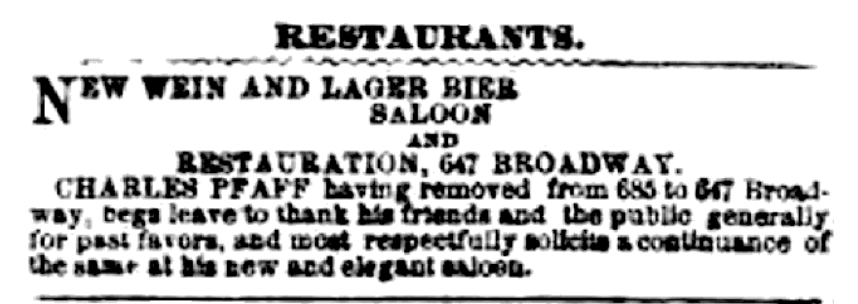

What this sequence of events means is that when Walt Whitman climbed down a narrow staircase into the subterranean space of Pfaff’s cellar at 647 Broadway  in the winter of 1859, the place was still very new. It had only been open at this location for approximately six months—since the end of March 1859.1 In a removal notice that appeared in T he New York Herald on March 31, 1859, Charles Pfaff described the cellar as a “New Wein and Lager Bier Saloon and Restauration” (See Figure 1, Appendix A).2 In addition to his announcement about this move to a larger and better space, Pfaff includes a message to all his previous customers as part of the notice: “CHARLES PFAFF ha ving removed from 685 to 647 Broadway, begs leave to thank his friends and the public generally for past favors, and most respectfully solicits a continuance of the same at his new and elegant saloon.”3 This notice, therefore, not only signals the closure of his former eating house, but it also functions as the first advertisement for what would soon become his most famous cellar.

in the winter of 1859, the place was still very new. It had only been open at this location for approximately six months—since the end of March 1859.1 In a removal notice that appeared in T he New York Herald on March 31, 1859, Charles Pfaff described the cellar as a “New Wein and Lager Bier Saloon and Restauration” (See Figure 1, Appendix A).2 In addition to his announcement about this move to a larger and better space, Pfaff includes a message to all his previous customers as part of the notice: “CHARLES PFAFF ha ving removed from 685 to 647 Broadway, begs leave to thank his friends and the public generally for past favors, and most respectfully solicits a continuance of the same at his new and elegant saloon.”3 This notice, therefore, not only signals the closure of his former eating house, but it also functions as the first advertisement for what would soon become his most famous cellar.

The New York Herald removal notice offers evidence both of Pfaff’s proficiency in multiple languages and of his desire to attract customers of German and French origins because he includes the German spellings of “bier” and “wein” and the French word “Restauration.” Pfaff’s use of “Restauration,”  a term closely related to “Restaurant” may reflect his interest in French wines and cuisine, as well as his time as a waiter in Switzerland since, as Karen Karbiener points out, “Restauration” is “still used today to designate less formal eateries in Switzerland and France.”4 But even more significantly, the notice provides approximate dates for Pfaff’s move in late March from 685 Broadway to the basement location at 647 Broadway, an address where Pfaff was already operating his business by March 31, 1859. Pfaff’s saloon would remain here during the three years that Walt Whitman frequented it before he left New York for Virginia and then the Civil War hospitals, and it continued at this location until 1864, the year before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox.

a term closely related to “Restaurant” may reflect his interest in French wines and cuisine, as well as his time as a waiter in Switzerland since, as Karen Karbiener points out, “Restauration” is “still used today to designate less formal eateries in Switzerland and France.”4 But even more significantly, the notice provides approximate dates for Pfaff’s move in late March from 685 Broadway to the basement location at 647 Broadway, an address where Pfaff was already operating his business by March 31, 1859. Pfaff’s saloon would remain here during the three years that Walt Whitman frequented it before he left New York for Virginia and then the Civil War hospitals, and it continued at this location until 1864, the year before the Confederate surrender at Appomattox.

An article published in the New-York Saturday Press described the location of Pfaff’s new saloon and gave instructions for getting there as follows:

On the shore of that sea which is always troubled, and tossing in a madness of omnibuses and targe t-shooters, and men, women, and children who are too late for something—Broadway—but far enough removed to catch only the hoarse echoes of its multitudinous thunder . . . there is a saloon.5

Pfaff’s, then, was on the shoreline; it was a liminal space of shifting sands and constant flux, where the tumultuous sea of Broadway stopped and the dry land upon which the shops and restaurants stood, began. Here, Pfaff’s seems to be a place outside of time, away from the omnibuses and people who are forever rushing on to their next destination or appointment. In fact, because it was situated below street level, the cellar could also offer a welcome respite for writers, artists, and tourists alike to hide out in between attempts to navigate the city streets.

Recent studies of international and American Bohemias, respectively, define the very concept of “Bohemia” in language that is similar to the New-York Saturday Press reporter’s attempts to describe Pfaff’s and its location. Daniel Cottom, for example, points out that Bohemia is “outcast in time as well as geography,” while J oanna Levin shows how American Bohemia “functioned as a liminal terrain,” a site from which to re- examine “bourgeois work and leisure ethics, gender roles and spiritual commitments.”6 In effect, by mapping Pfaff’s onto the shoreline, the reporter positions the cellar as a locus within and simultaneously separate from New York City. As a result Pfaff’s becomes a site where Clapp and the American Bohemian coterie could rethink and ultimately challenge some of the aforementioned “habits of dress, speech, and thought” that characterize the lives of those families—those men, women, and children passing overhead on Broadway.

Yet, according to the Press, Pfaff’s  was not simply positioned at the intersection of sand and ocean; entering it was like venturing into an undersea realm. The writer goes so far as to equate the cellar’s rooms to “some coral home of happy mermaids, right below the distracted main.” Here, the reporter presents the cellar as a well-kept secret locale, where patrons drank and conversed in their own underground society, just below the “chaotic” city and the “distracted” crowds. Nothing of “light-house alluring significance” directed patrons t o the cellar. There was merely a “modest” sign posted outside the building on which the words “Pfaff” and “Restauration” were only “faintly” discernable.7 To put it mildly, Pfaff’s was not the easiest place to find or access. But those literary and artistic patrons who were in the know, so to speak, were quite familiar with how to steer themselves through the crowds, and nightly, they set a direct course for the saloon. Once prospective customers saw the sign and descended a set of steps leading from the street above to the baseme nt below, they found themselves, at last, inside Charles Pfaff’s basement. One of the first persons they likely met when they entered was the proprietor himself.8 Pfaff could most often be found behind the bar, where he kept “a watchful eye on the few uneven stairs, which led to the crowded sidewalk, ready to great a distinguished visitor” with the offer of a meal or a drink.9

was not simply positioned at the intersection of sand and ocean; entering it was like venturing into an undersea realm. The writer goes so far as to equate the cellar’s rooms to “some coral home of happy mermaids, right below the distracted main.” Here, the reporter presents the cellar as a well-kept secret locale, where patrons drank and conversed in their own underground society, just below the “chaotic” city and the “distracted” crowds. Nothing of “light-house alluring significance” directed patrons t o the cellar. There was merely a “modest” sign posted outside the building on which the words “Pfaff” and “Restauration” were only “faintly” discernable.7 To put it mildly, Pfaff’s was not the easiest place to find or access. But those literary and artistic patrons who were in the know, so to speak, were quite familiar with how to steer themselves through the crowds, and nightly, they set a direct course for the saloon. Once prospective customers saw the sign and descended a set of steps leading from the street above to the baseme nt below, they found themselves, at last, inside Charles Pfaff’s basement. One of the first persons they likely met when they entered was the proprietor himself.8 Pfaff could most often be found behind the bar, where he kept “a watchful eye on the few uneven stairs, which led to the crowded sidewalk, ready to great a distinguished visitor” with the offer of a meal or a drink.9

Even though the aforementioned  newspaper writer discussed Pfaff’s in decidedly o ceanic terms, the 647 Broadway location was most often referred to as “the cave.” It was modeled on underground rathskellers and grottos—popular drinking and eating- houses in Europe.10 The journalist and novelist Joseph Lewis French called the New York n ightspot the “American Mermaid” and also compared it to Ben Jonson’s “Apollo,” where the “mighty men of Elizabeth” had gathered during the English Renaissance.11 Bayard Taylor, a poet and occ asional visitor to the beer cellar, thought the “dim, smoky, confidential atmosphere” of Pfaff’s was more like Auerbach’s cellar in Leipzig.12 With its low ceilings, stone walls, and even a few barrels and hogsheads scattered throughout the rooms, it is not surprising that the beer cellar’s literary patrons would liken it to taverns in England and Germany, where gifted writers had gathered in centuries past. It also seems fitting that the newspaper editor Charles Congdon would see Pfaff’s, the center of American Bohemia, somewhat romantically, as “quite mediæval and gypsy-like.”13 Congdon’s words connect th e American Bohemians and their gathering place to the young artists, also referred to as Bohemians, in Paris in the 1830s who adopted medieval dress and speech to express their opposition to tradition.14 The Old World atmosphere at Pfaff’s, then, might be attributed both to the décor of the cellar and to the lifestyle of the French Bohemians and artists whose practices the American Bohemians subsequently imported.

newspaper writer discussed Pfaff’s in decidedly o ceanic terms, the 647 Broadway location was most often referred to as “the cave.” It was modeled on underground rathskellers and grottos—popular drinking and eating- houses in Europe.10 The journalist and novelist Joseph Lewis French called the New York n ightspot the “American Mermaid” and also compared it to Ben Jonson’s “Apollo,” where the “mighty men of Elizabeth” had gathered during the English Renaissance.11 Bayard Taylor, a poet and occ asional visitor to the beer cellar, thought the “dim, smoky, confidential atmosphere” of Pfaff’s was more like Auerbach’s cellar in Leipzig.12 With its low ceilings, stone walls, and even a few barrels and hogsheads scattered throughout the rooms, it is not surprising that the beer cellar’s literary patrons would liken it to taverns in England and Germany, where gifted writers had gathered in centuries past. It also seems fitting that the newspaper editor Charles Congdon would see Pfaff’s, the center of American Bohemia, somewhat romantically, as “quite mediæval and gypsy-like.”13 Congdon’s words connect th e American Bohemians and their gathering place to the young artists, also referred to as Bohemians, in Paris in the 1830s who adopted medieval dress and speech to express their opposition to tradition.14 The Old World atmosphere at Pfaff’s, then, might be attributed both to the décor of the cellar and to the lifestyle of the French Bohemians and artists whose practices the American Bohemians subsequently imported.

Charles Pfaff took great pride in his “mediæval” saloon, but the cellar’s interior provided a stark contrast to larger restaurants and to some of the popular New York oyster cellars, which were furnished in far more luxurious and updated styles. According to  Artemus Ward, nearly all of the fashionable oyster cellars had a marble countertop, where customers could order drinks and another counter where oysters were served. He recalled, “[At the oyster cellar] there are sure to be about a dozen boxes or alcoves, each furnished with its little table and wel l stuffed seats, to exclude the occupant from view of other customers.” Some oyster cellars even had “one or two, if not more, cabinets or private rooms for parties wishing to sup quietly.”15 Charles McKay, editor of the Illustrated London News, reported: “In Walking up Broadway by day or by night—but more es pecially by night—the stranger cannot but be struck by the great number of ‘Oyster Saloons,’ ‘Oyster and Coffee Saloons,’ and ‘Oyster and Lager Beer Saloons.’”16 He also took notice of New York’s numerous drinking houses, observing that many were “like the drinking saloons in Germany, situated in vaults or cellars, with steps from the street.” In contrast to the earlier German cellars upon which they are based, the city’s American versions were often located in “underground stories of stately commercial palaces of granite, brown s tone, or white,” a statement that seems at least partially applicable to Pfaff’s establishments in the sense that he operated a series of basement saloons situated beneath other businesses.17

Artemus Ward, nearly all of the fashionable oyster cellars had a marble countertop, where customers could order drinks and another counter where oysters were served. He recalled, “[At the oyster cellar] there are sure to be about a dozen boxes or alcoves, each furnished with its little table and wel l stuffed seats, to exclude the occupant from view of other customers.” Some oyster cellars even had “one or two, if not more, cabinets or private rooms for parties wishing to sup quietly.”15 Charles McKay, editor of the Illustrated London News, reported: “In Walking up Broadway by day or by night—but more es pecially by night—the stranger cannot but be struck by the great number of ‘Oyster Saloons,’ ‘Oyster and Coffee Saloons,’ and ‘Oyster and Lager Beer Saloons.’”16 He also took notice of New York’s numerous drinking houses, observing that many were “like the drinking saloons in Germany, situated in vaults or cellars, with steps from the street.” In contrast to the earlier German cellars upon which they are based, the city’s American versions were often located in “underground stories of stately commercial palaces of granite, brown s tone, or white,” a statement that seems at least partially applicable to Pfaff’s establishments in the sense that he operated a series of basement saloons situated beneath other businesses.17

Although Pfaff called his newest establishment “an elegant saloon,” it was more often remembered for its food and drinks, the sounds of loud voices and laughter, and the smell of smoke from the kitchen and from customers’ pipes than for its decor. As poet and Whitman admirer  Richard Henry Stoddard explained, Pfaff’s, unlike the oyster saloons, was not such a “spick-span” place; it did not sport white walls, and it had tables rather than a section of stalls.18 The same writer that located Pfaff’s deep beneath the “sea” of Broadway also deemed the beer cellar “a plain place . . . unhung wit h the pictures of masters [and] unsoftened by carpet.” Pfaff’s lacked “perfumed rooms,” and there was no “elegant music” playing while its customers drank and dined.19 Unlike the moder n restaurants and barrooms that were clean, carefully decorated, and well lit, Pfaff’s had no “mirror-lined walls, richly carved apartments, carpeted floors, [or] flashing electric lights.”20 In the words of one Pfaffian, the beer cellar “was a hole beneath the surface of the street, ill-lighted, ill-ventilated, and ill-kept.”21

Richard Henry Stoddard explained, Pfaff’s, unlike the oyster saloons, was not such a “spick-span” place; it did not sport white walls, and it had tables rather than a section of stalls.18 The same writer that located Pfaff’s deep beneath the “sea” of Broadway also deemed the beer cellar “a plain place . . . unhung wit h the pictures of masters [and] unsoftened by carpet.” Pfaff’s lacked “perfumed rooms,” and there was no “elegant music” playing while its customers drank and dined.19 Unlike the moder n restaurants and barrooms that were clean, carefully decorated, and well lit, Pfaff’s had no “mirror-lined walls, richly carved apartments, carpeted floors, [or] flashing electric lights.”20 In the words of one Pfaffian, the beer cellar “was a hole beneath the surface of the street, ill-lighted, ill-ventilated, and ill-kept.”21

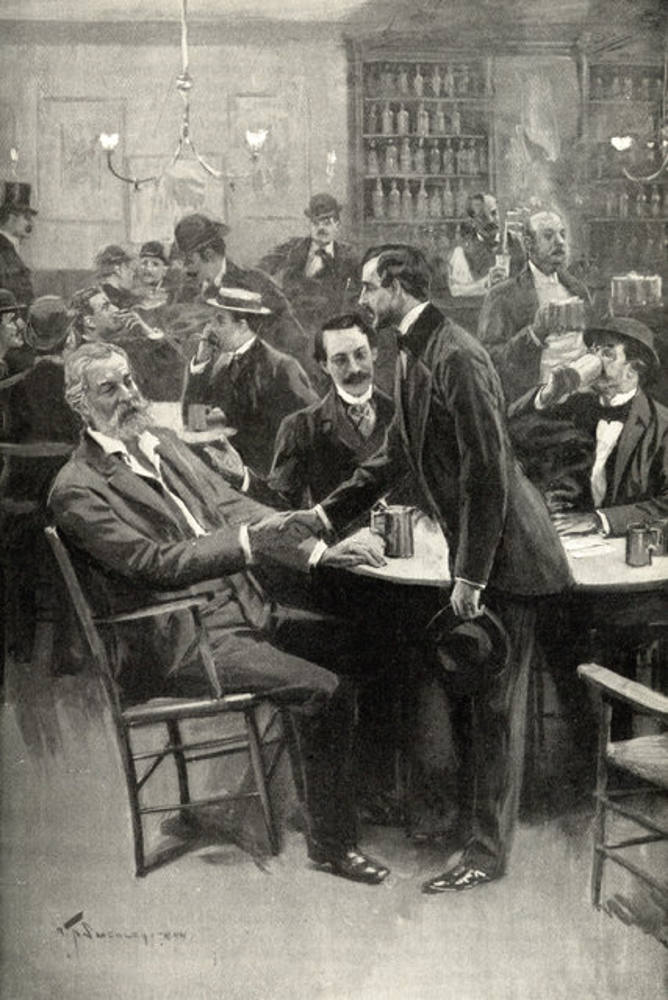

Once patrons stepped into Pfaff’s cellar, they found themselves inside a large apartment beneath the Coleman House Hotel. According to Karen Karbiener, “the distinguishing feature of the interior of Pfaff’s was the division of its space into two distinct rooms: the main room of the saloon and an area below the vaulted sidewalk of Broadway.”22 The dimly lit main room was furnished with a bar and a few tables and chairs.23 Even Artemus Ward, who was quite fond of Pfaff’s, admitted that the “furnishings were rough . . . a counter, shelves, [and] some barrels.”24 Likewise,  William Winter, another associate of the Bohemian group, recalled that Pfaff’s had “dirt floors” and similarly noted that the “cellar’s rooms were roughly and rather sparsely furnished.”25 Several form er beer cellar patrons, presumably referring to the main room, report that it contained “a barroom counter that was perpetually covered with suds, a few shelves, some barrels and a single clock.”26 Beyond the bar, the vault “stretched lengthwise to the right of the staircase.”27 This arrangement allowed customers to order their drinks at the bar before taking a seat in the main room of the saloon or, as was the case with Whitman and the American Bohemians, before retiring to the vault.

William Winter, another associate of the Bohemian group, recalled that Pfaff’s had “dirt floors” and similarly noted that the “cellar’s rooms were roughly and rather sparsely furnished.”25 Several form er beer cellar patrons, presumably referring to the main room, report that it contained “a barroom counter that was perpetually covered with suds, a few shelves, some barrels and a single clock.”26 Beyond the bar, the vault “stretched lengthwise to the right of the staircase.”27 This arrangement allowed customers to order their drinks at the bar before taking a seat in the main room of the saloon or, as was the case with Whitman and the American Bohemians, before retiring to the vault.

The vault at Pfaff’s was “a special room, arched at the top” with “a weird, dull, and gloom y appearance” that extended under the sidewalks of Broadway. In the middle of the space, Pfaff had installed a large table that was reserved especially for the use of the American Bohemian group.28 This table accommodated between fifteen and thirty persons, and Henry Clapp, Jr., could often be found sitting at the head of it.29 In her novel, “A Long Journey” (1867), Rebecca Harding Davis offers a detailed portrait of the vault portion of Pfaff’s, characterizing it as a small alcove with wine barrels against the walls and the a pine table around which the Bohemians assembled. She went on to explain that the entrance to the vault opened into the outer room, offering “a glimpse of similar tables about which were gathered some quiet Dutch workmen.”30 This description is strikingly similar to the barroom scene Whitman presents in Calamus #29:

ONE flitting glimpse, caught through an interstice,

Of a crowd of workmen and drivers in a bar-room,

around the stove, late of a winter night—And

I unremarked, seated in a corner;

Of a youth who loves me, and whom I love, silently

approaching, and seating himself near, that he

may hold me by the hand;

A long while, amid the noises of coming and going

—of drinking and oath and smutty jest,

There we two, content, happy in being together,

speaking little, perhaps not a word.31

Whitman gives his readers a single, brief look at a barroom through the eyes of the poem’s persona (the “I”) who appears to be one of its male patrons. The poet’s lines suggest that the persona is seated in one room or corner of a barroom, which could be Pfaff’s cellar, and hears the usual sounds of “coming and going” as he watches the other beer-cellar regulars, trying to get a look, even if only briefly, at the workers and drivers enjoying an evening of drink and conversation in another area of the bar. The vantage point that Whitman gives his poetic persona is consistent with both Harding-Davis’s fictional portrait of Pfaff’s and with the fact that Pfaff’s may have consisted of both a vaulted space reserved for the Bohemians and another main seating area with a bar. If there was, indeed, a curtain separating the two spaces, then it is tempting to speculate that Whitman’s “one flitting glimpse” through an interstice might have been what the poetic persona could see of a group of workmen congregating around a stove through the gap in that curtain. In either case, it seems as if the persona is looking out from one room of Pfaff’s in an attempt to see what is happening in the other.

Even though the Bohemians may have had seats reserved for them in the vault portion of the restaurant, it is quite certain that Pfaff’s rooms were not as clean nor were the chairs as comfortable as some customers might have lik ed. Since the cellar was but “ill-ventilated,” the rooms would have been filled with smoke because food was constantly being prepared and many of the customers enjoyed Pfaff’s cigars.32 The Eastern State Journal described the most prevalent odor of that “queer Bohemian land” at Pfaff’s as “the fragrance of tobacco smoked in pipes of every style, from the red-clay to the meerachaum.”33 Journalist John Swinton, an occasional visitor at the beer cellar, we nt so far as to nickname it “Pfaff’s privy” because it “smelled atrociously” and even Artemus Ward acknowledged that parts of the cellar looked “somewhat unsavoury.”34 At the same time , because Pfaff’s was below street-level, it “was always very nearly dark, even in the daytime”; one account suggests that the establishment was lit only by a “single gaslight.”35

It is also unlikely that Pfaff’s was the kind of place that offered the American Bohemians and the other beer cellar patrons much peace and quiet since, according to Whitman; the Pfaffians were rowdy and loud themselves. However, they also heard far more than what the New-York Saturday Press writer had called the “hoarse echoes” of the city above while they sat at Pfaff’s tables.36 Whitman’s poem the “The Two Vaults” points out the boisterousness of Pfaff’s patrons as they “eat and drink and carouse,” and the poet even implies that visitors to Pfaff’s are expected to “Drink wine—drink beer— raise [their] voice,” in order to call out greetings that would be audible to fellow Pfaffians as soon as they appear on the upper step and begin their descent into the cellar (See Figure 1, Appendix B). Whitman also emphasizes the non-stop noise of the “continual crowds” walking on the street above when he writes, “overhead, pass the myriad feet of Broadway.” Lloyd Morris offers a similar interpretation of what the Pfaffian s might have been able to hear from the streets above: “The noise of the afternoon promenade on Broadway drifted down into the cave, and at night, it echoed [with] the Niagara roar of omnibuses.”37

It is also unlikely that Pfaff’s was the kind of place that offered the American Bohemians and the other beer cellar patrons much peace and quiet since, according to Whitman; the Pfaffians were rowdy and loud themselves. However, they also heard far more than what the New-York Saturday Press writer had called the “hoarse echoes” of the city above while they sat at Pfaff’s tables.36 Whitman’s poem the “The Two Vaults” points out the boisterousness of Pfaff’s patrons as they “eat and drink and carouse,” and the poet even implies that visitors to Pfaff’s are expected to “Drink wine—drink beer— raise [their] voice,” in order to call out greetings that would be audible to fellow Pfaffians as soon as they appear on the upper step and begin their descent into the cellar (See Figure 1, Appendix B). Whitman also emphasizes the non-stop noise of the “continual crowds” walking on the street above when he writes, “overhead, pass the myriad feet of Broadway.” Lloyd Morris offers a similar interpretation of what the Pfaffian s might have been able to hear from the streets above: “The noise of the afternoon promenade on Broadway drifted down into the cave, and at night, it echoed [with] the Niagara roar of omnibuses.”37

Given the smell, the noise, and the rough furnishings at Pfaff’s, it is hard not to wonder what it was that actually drew both a literary and a French and German speaking crowd to this particular cellar. After all, Charles Pfaff’s basement  was one among many establishments on Broadway. In 1859, the very year that Pfaff moved to the 647 address, there was no shortage of saloons for Henry Clapp, Jr., Fitz James O’B rien, and the American Bohemian group to choose from. They could have become regulars at Taylor’s Saloon at 555 Broadway, an establishment Walt Whitman had visited with the writer Bronson Alcott.38 They could have gone to Thompson’s Saloon located on the lower floor of 359 Broadway, which also housed

was one among many establishments on Broadway. In 1859, the very year that Pfaff moved to the 647 address, there was no shortage of saloons for Henry Clapp, Jr., Fitz James O’B rien, and the American Bohemian group to choose from. They could have become regulars at Taylor’s Saloon at 555 Broadway, an establishment Walt Whitman had visited with the writer Bronson Alcott.38 They could have gone to Thompson’s Saloon located on the lower floor of 359 Broadway, which also housed  Brady’s Daguerreotype Gallery .39 There were more than ten oyster and/or lager bier saloons within walking distance of Pfaff’s, including Antonio Cabrol’s lager bier saloon, (422 1&f rasl;4 Broadway), William H. Skinner’s Oyster Saloon (426 Broadway), Jahr & Fiedler’s lager beer saloon (418 Broadway), and Joseph Riley’s saloon and eating house at 600 Broadway.40 And it is likely that many of these saloons would have actually been more convenient to enter and patronize than Pfaff’s. After all, Karen Karbiener notes that because Pfaff’s was beneath the Coleman House, the beer cellar’s American Bohemian clientele may not have allowed to walk though the hotel’s “elegant main floor” at all hours. She suggests that they could only enter the beer cellar after 5PM via the set of stairs that descended from the sidewalk and into the vault.41 Yet, even though entrance to the cellar may have required putting up with this inconvenience, Pfaff’s soon became the Bohemians’ favorite New York hangout.

Brady’s Daguerreotype Gallery .39 There were more than ten oyster and/or lager bier saloons within walking distance of Pfaff’s, including Antonio Cabrol’s lager bier saloon, (422 1&f rasl;4 Broadway), William H. Skinner’s Oyster Saloon (426 Broadway), Jahr & Fiedler’s lager beer saloon (418 Broadway), and Joseph Riley’s saloon and eating house at 600 Broadway.40 And it is likely that many of these saloons would have actually been more convenient to enter and patronize than Pfaff’s. After all, Karen Karbiener notes that because Pfaff’s was beneath the Coleman House, the beer cellar’s American Bohemian clientele may not have allowed to walk though the hotel’s “elegant main floor” at all hours. She suggests that they could only enter the beer cellar after 5PM via the set of stairs that descended from the sidewalk and into the vault.41 Yet, even though entrance to the cellar may have required putting up with this inconvenience, Pfaff’s soon became the Bohemians’ favorite New York hangout.

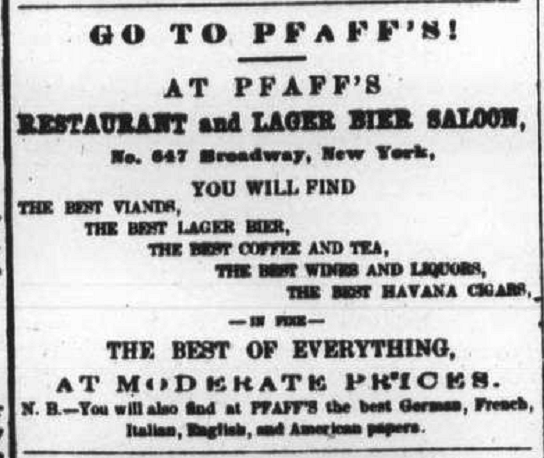

Pfaff’s, as Clapp and the Bohemians soon learned, had much to recommend it. The cellar’s location on Broadway near Bleecker Street meant it was in the heart of a rapidly expanding American city, but this address also contributed to the “European character” of the place since at least by the 1860s and 1870s this area was “more characteristic of Paris than of New York . . . it remind[ed] one strongly of the Latin Quarter.”42 Furthermore, Pfaff took pride in offering his customers imported products such as German beer and Cuban cigars. According to an advertisement published in both the Saturday Press and in the humor magazine Vanity Fair, Pfaff’s had “the best viands, the best lager bier, the best coffee and tea, [and] the best Havana cigars” (See  Figure 2, Appendix A). The bar owner also p rovided his patrons with up-to-date reading material, namely a wide selection of local periodicals and international newspapers, which contributed to the “worldliness” of the establishment.43 In other words, he not only offered customers copies of The Press and Vanity Fair, but he was also known to grant them access to news in German, French, and Italian, as well as British and American English.44 According to the New York Evening Express, by 1867, Pfaff obtained at least some of these papers from Austrian-born newspaper dealer August Brentano: “[T]he most famous foreign newspapers are always to be had of Brentano—and he has among his subscribers not only the leading residents of Fifth avenue and his vicinity, but the principal Hotels and restaurants, from the New York to the Brevoort, and from Delmonico’s to Pfaff.”45

Figure 2, Appendix A). The bar owner also p rovided his patrons with up-to-date reading material, namely a wide selection of local periodicals and international newspapers, which contributed to the “worldliness” of the establishment.43 In other words, he not only offered customers copies of The Press and Vanity Fair, but he was also known to grant them access to news in German, French, and Italian, as well as British and American English.44 According to the New York Evening Express, by 1867, Pfaff obtained at least some of these papers from Austrian-born newspaper dealer August Brentano: “[T]he most famous foreign newspapers are always to be had of Brentano—and he has among his subscribers not only the leading residents of Fifth avenue and his vicinity, but the principal Hotels and restaurants, from the New York to the Brevoort, and from Delmonico’s to Pfaff.”45

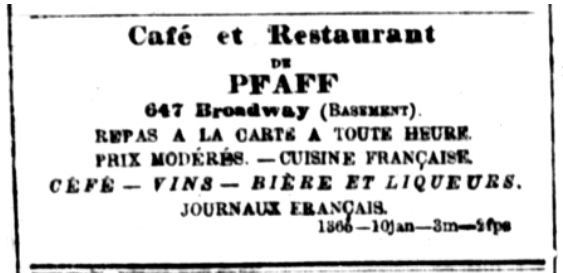

It is important to point out, however, that even though Pfaff offered a selection of foreign newspapers in several European languages, it is clear that he actively sought out and attempted to maintain a French-speaking clientele. As early as 1862, he began what would become a long-standing advertising relationship with t he Courrier des Etats-Unis, a French language newspaper published by French immigrants in New York. In January 1862 he promoted his “Café et Restaurant De PFAFF 647 Broadway (BASEMENT).”46 In this advertisement he draws attention to his stores of wine and beer, the selection of French cuisine served in the cellar, and to the French newspapers that his customers might peruse while drinking coffee or eating a hot meal (See  Figure 3, Appendix A). He also promised his patrons that the cellar’s foods and drinks were available at “Prix Modérés” or “Moderate Prices.” In 1864 and 1865 notices and/or ads for his next place at 653 Broadway also appeared in the Cour rier, and even his final location, at 9 W. 24th Street was advertised in the paper as a “Restaurant Francais” [trans. French Restaurant] rather than a German one in the late 1870s.47

Figure 3, Appendix A). He also promised his patrons that the cellar’s foods and drinks were available at “Prix Modérés” or “Moderate Prices.” In 1864 and 1865 notices and/or ads for his next place at 653 Broadway also appeared in the Cour rier, and even his final location, at 9 W. 24th Street was advertised in the paper as a “Restaurant Francais” [trans. French Restaurant] rather than a German one in the late 1870s.47

Pfaff’s advertising practices and his efforts over many years to keep reading materials in a variety of languages on hand in his establishments suggest the diversity, multiculturalism, and multilingualism of his regular patrons. It is likely a visitor to Pfaff’s would hear conversations in several languages taking place among other customers and/or between Charles Pfaff himself and his staff and patrons on a daily basis. Any patron of Pfaff’s, then, might expect the cellar to have the reading material, as well as the ambiance and conversation of a European salon. Pfaff’s would also come to embody its proprietor’s own European cultural background and work experiences since it functioned as both a German lager cellar and a restaurant with French cuisine and imported wines that likely reflected his time and training in Switzerland. It is not surprising that, upon visiting Pfaff’s, Henry Clapp was inspired to form an American Bohemian group since Pfaff’s place seemed designed to appeal to just such a crowd of writers, actors, and artists who favored French Bohemianism. The worldliness of Pfaff’s almost certainly endeared the cellar to the future King of Bohemia. And it was this vibrant environment—with its hint of Old World mystery, its foreign atmosphere, its eccentric American Bohemian community, and its congenial host—that attracted an out-of-work, out-of-luck, and probably curious Walt Whitman along with many other literary and artistic patrons in 1859.

This page has paths:

- “GO TO PFAFF’S!” Audrey Clancy