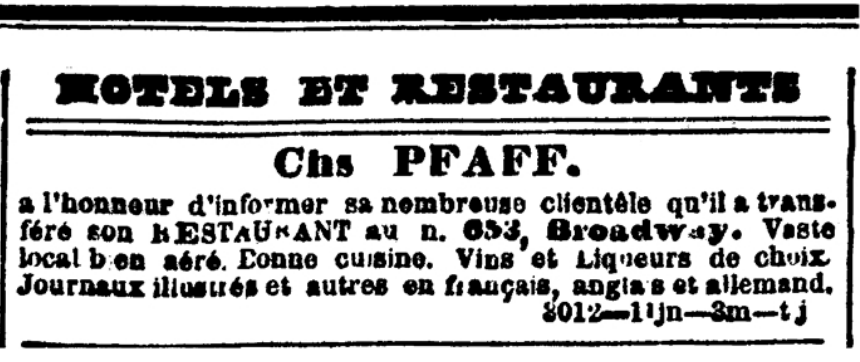

Charles Pfaff’s Restaurant at 653 Broadway

By June 1864, Pfaff informed some of his clientele about his new restaurant through a removal notice, similar to the one printed in the New York Herald when he relocated from 685 to 647 Broadway. Only this time, the removal notice, the only one of its kind that has come to light thus far, appeared in French, again in the Courrier des Etats-Unis: “Chs. Pfaff. [A] l’honneur d’informer sa nombreuse clientêle qu’il a transféré son RESTAURANT au n. 653, Broadway.” [Trans. “Charles Pfaff has the honor to inform his numerous customers he transferred his Restaurant to No. 653 Broadway”] (See

Pfaff continued to advertise his cellar at 647 Broadway in the Albion Magazine from May 7th through July 9, 1864.5 It is possible then that the two Broadway locations were open simultaneously for a short period of time during the spring and summer of 1864 until the transition to 653 Broadway could be completed. Approximately one year later, by August 1865, advertisements for the restaurant at the new address proclaimed Pfaff’s “the most celebrated restaurant in the country” and promised “The Best Waiters, The Best Company, and The Best of Everything.”6 These ads served to further distinguish the new place from the old because the term “restaurant and dining rooms” was used to describe 653 Broadway instead of the former “wein and lager bier saloon,” a move perhaps indicative of Pfaff’s efforts to expand his business and appeal to a broader clientele.

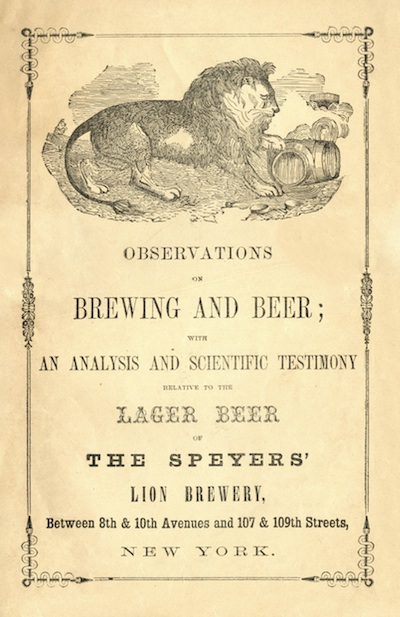

Whereas the cellar in which the Bohemians met was often called “the cave” or the “vault,” Pfaff named his new restaurant “Löwengrube,” or the Lion’s Den, a name that may have been related to the fact that his former American Bohemian patrons were sometimes referred to as “the lions of Bohemia,” depending on when and where the group’s nickname originated.7 The name for the restaurant may have also come from Pfaff’s seeming preference for Speyers lager bier because the beer’s home was the

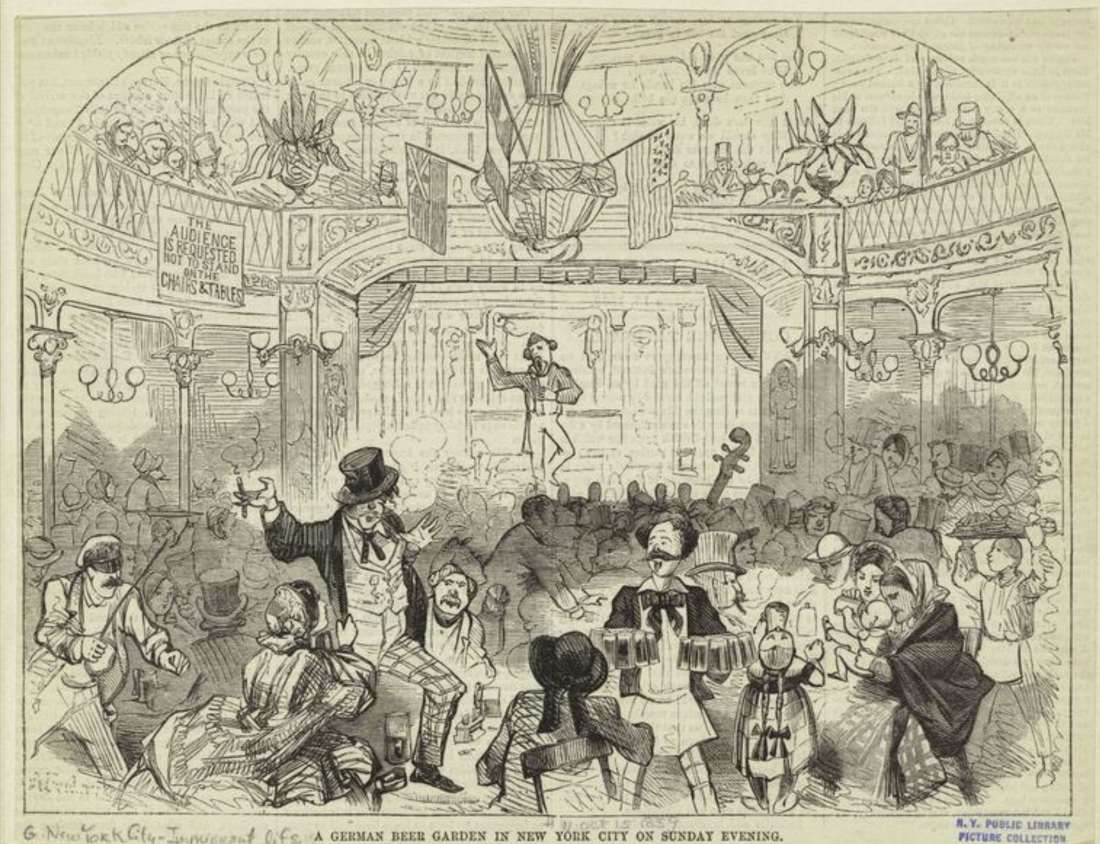

In the summer of 1865, Pfaff came up with the idea to add another feature to the restaurant, which, in later advertisements, would be referred to as a “summer garden.” According to the Milwaukee Sentinel, a so-called German garden was “generally compressed in a currant bush stuck in a fig box, a titled keg of lager, and a gutter at the back door” or amounted, according to Junius Browne, to little more than “a hole in a roof, a fir-tree in a tub, and a sickly vine or two in a box.” Pfaff’s “summer garden,” however, was not one of the aforementioned typical “ German gardens.” In fact, James Ford saw several green vines and an attractive awning at Pfaff’s.10 But the best description of these features comes from Night Side of New York, which explains how Pfaff turned an open yard into a version of “an intramural garden with wonderful trees and shrubs, some of which are real from the root to the height of a foot or so.” At this point the plants “were then continued by brush of scenic artist to any height, upon the wall.” A notice in the Saturday Press proclaimed that Pfaff’s had been much improved by this “beautiful landscape,” as well as by the garden.11 This “landscape” was actually the work of an artist from the Winter Garden theatre on a wall “up which . . . Pfaff’s climbing plants never could have made their way, but for the illusion wrought by the same magic

With these attractions, Pfaff managed to turn his restaurant into a resort, the perfect place to gather on spring and summer evenings. Pfaff even installed a canopy over the garden area with a canvas awning to protect customers and staff from unexpected summer thunderstorms:

[I]t is a curious scene to behold Captain Pfaff, when a heavy thunder shower is coming up from leeward, giving the word, as if from the quarter-deck, for all hands to hoist sail, and to see the German waiters going up rigging, and belaying, and hauling in slacks, and letting go sheets, and doing fifty other very salt and maritime things, with a view to getting the piece of canvas into a position for staving off the storm.12Here, Pfaff’s waiters are again portrayed as an efficient brigade, even the crew of the tight ship that Pfaff ran, (one can almost hear him calling for all hands on deck) in order to enable customers to continue enjoying their meals, rain or shine. In addition to the garden and the awning, James Ford pointed out another attraction that would have certainly amazed Pfaff’s guests. Ford claims that in one corner of Pfaff’s outdoor garden there was “an American Eagle that was tethered to one of the posts in the rear of the saloon.” According to Ford, Pfaff fed the bird “the standard German fare of pretzels and sauerkraut” so that “the National bird received the same nourishment as American arts and letters, and was fed with the same generous hand.”13

Advertisements during the second run of the New-York Saturday Press in 1865 do not mention the eagle if it ever existed; however, they did promote the new garden, suggesting that everyone who “comes to town goes at once to Pfaff’s” because it has “the coolest and pleasantest summer garden in the city.”14 At that time, Pfaff’s attracted its regular customers, including a “large foreign element” and “a number of dramatic critics, and people connected with the neighboring theatres,” particularly the Winter Garden.15 The theater crowd, after all, would have been eager to see the “landscape” created by one of their own artists.16 In addition to these men and women from the theaters, a few “literary lights” from the American Bohemian crowd continued to patronize the place along with “French refugees and artists.”17 It is clear then that during the middle and late 1860s Pfaff’s became known for its summer garden, and the cellar restaurant became a must-see tourist attraction, a place with a reputation good enough to make one want to stop in for a drink even if he or she was merely passing through New York.