“Let’s Go To Kruyt’s”: Selling Pfaff’s

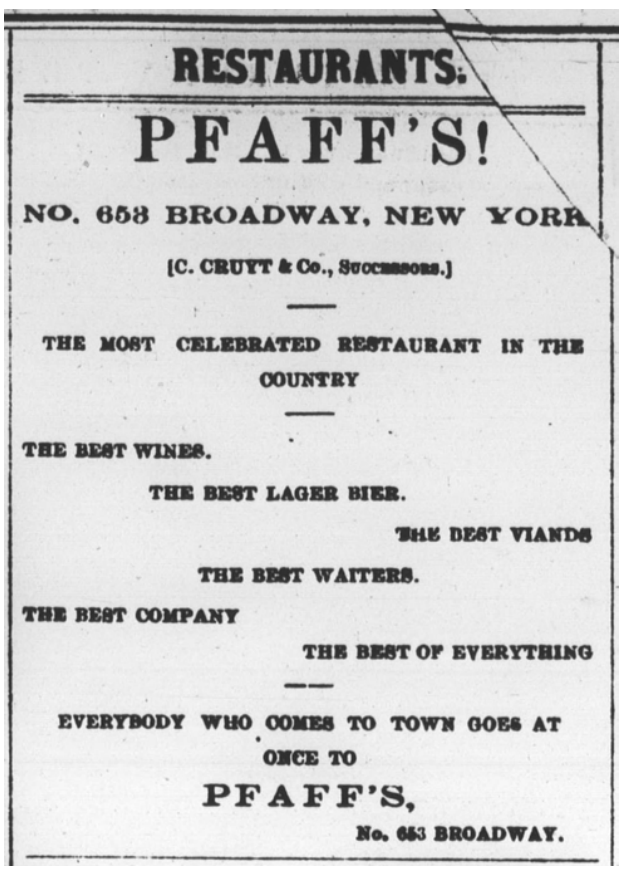

Then, suddenly, in 1866, only two years after Pfaff moved to 653 Broadway and only a little more than a year after he had likely dedicated time, effort, and expense to adorning the place with the attractive summer garden feature, the advertisements for Pfaff’s Restaurant printed in Henry Clapp’s New-York Saturday Press announced what seems to have been an unexpected change. Now, a new line appeared on each ad beneath Pfaff’s name: “C. Cruyt & Co., Successors,” thereby indicating that Pfaff was leaving his restaurant and Cruyt (also spelled Kruyt) would be taking over (See Figure 9, Appendix A).1

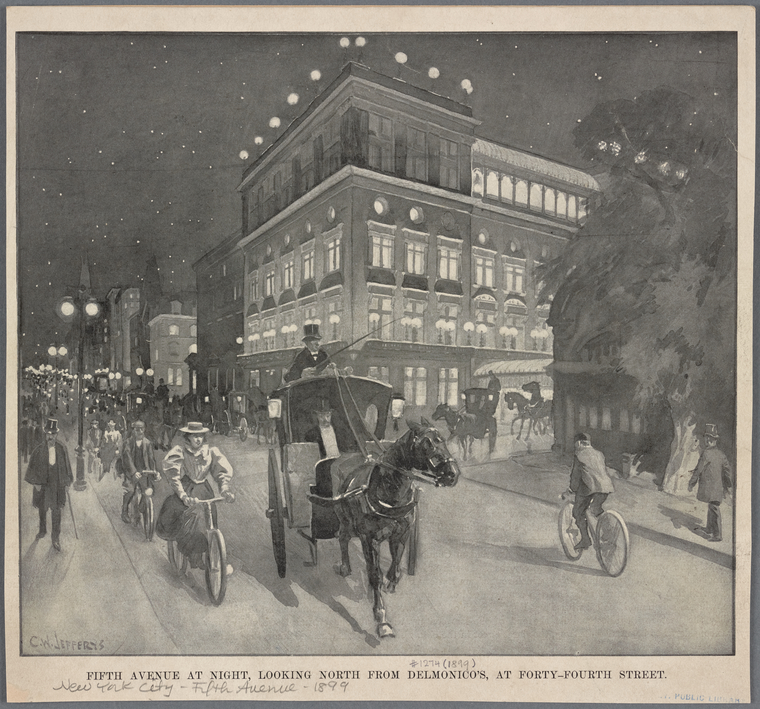

Why Pfaff decided to get out of the restaurant business at this particular time remains a mystery. The notice about Cruyt’s succession first appeared on March 24, 1866, just over four and half months after the last Confederate surrender to Union forces on November 6, 1865, and at a time when Civil War soldiers were in the process of returning or had recently arrived home. Artist and Pfaff’s regular Elihu Vedder suggested that the then forty-seven-year-old restaurateur simply may have wanted to enjoy the financial success he had experienced at his Broadway establishments: “The time came when [Pfaff] retired to the country well off; but then the time also came when he returned and started another place further up-town.”2 A surprised and angry Henry Clapp, Jr. wrote in the Press, “Well, I suppose he’s got rich and wants to lay off for a while.” The new owner Charles Cruyt was well known as either a manager or a chef de cuisine at Delmonico’s for more than a dozen years.3 In spite of his anger, Clapp admitted, “We shall sadly miss the genial face of dear old Pfaff, and the habitués of the place will drink to his memory as long as the house stands.”4 Since Pfaff spent so much time with the American Bohemians and had been so generous to them, it makes sense that Clapp and any other remaining members of the former Pfaff’s group would be particularly upset about the change. After all, the Bohemians had benefitted significantly from Pfaff’s generosity over the years, and the restaurant’s new proprietor would likely not have the same relationship with Clapp and his associates—at least not right away.

Yet, Pfaff seemed to have second thoughts about the business deal almost immediately. He did not really appear to leave entirely, preferring to remain a presence in the beer cellar even as the time approached for the business to change hands. According to Clapp, “Pfaff, by the way, still lingers about the place, welcome as ever to his old habitués

Clapp also indicated that just as Pfaff remained, seemingly holding fast to his establishment, Kruyt too, from the very beginning, had mixed feelings about Pfaff’s place: Kruyt, on the other hand, turns a wishful eye now and then back to Delmonico’s (where he was chef de cuisine for so long), but is getting gradually used to his new quarters, and maintains their prestige so well that soon it will be as natural to say “Let’s go to Kruyt’s,” as it has been for this ten years to say “Let’s go to Pfaff’s.”6 Clapp, if his dates are correct, indicates that he has had some connection to the restaurant for the previous decade, or since 1856, which lends support to the earlier discovery myths. Yet, Clapp expresses mixed feelings about Cruyt’s ability to replace Charles Pfaff as proprietor since he praised Kruyt, but also wrote, “[Pfaff’s] name still remains to us—a name known, now, all over the land—and it will be a long time before the establishment will be known by any other.””7 Clapp even went so far as to criticize Cruyt’s ability to manage the restaurant, telling his readers that soon after the deal was made with Cruyt, “Some people to be sure, don’t like the place, because, you know, some people have been kicked out.”8 Is this an indirect way of saying that Clapp himself has been asked to leave Cruyt’s? Perhaps it suggests that the American Bohemians or their associates are no longer welcome in the cellar at all hours. At any rate, this bad press from Clapp, particularly his implication that significant changes were being made in the way the needs and requests of customers were handled, was almost certainly the beginning of the end of the arrangement between Pfaff and Cruyt.

Clapp was at least partly right, as Pfaff’s place does not seem to have been known as “Cruyt’s” for very long since Pfaff’s absence from the restaurant business was not an extended one. By mid-October 1867, two years after having “sold out,” Captain Pfaff was back at the helm of his 653 Broadway establishment.9 A notice in the Courrier des Etats-Unis confirms Pfaff’s return: “C. PFAFF, RESTAURANT, 653 BROADWAY, Prévient sa nombreuse clientèle qu’il a repris la gérance de son ancient établissement” [Trans. [C. Pfaff] informs his large clientele that he has resumed the management of his old establishment]. Here, Pfaff points out that now he has regained control of the restaurant, and he reassures his customers that he will again offer “VINS, LIQUERS ET CIGARES de première qualité” [trans. Wines, Liquors, and Cigars of the best quality], just as he did before the establishment changed hands.10

An article entitled “The Secret of Success,” published in The Fireside Companion in February 1868 helps shed even more light on Pfaff’s dealings with Cruyt. First, the author praises Pfaff as a skilled businessman and describes the restaurateur’s success, noting that Pfaff’s “name has become as familiar from Maine to Georgia, as that of

[B]y attending personally to every department of the business, and having everything a little better than could be found in any other place of the kind, [Pfaff] succeeded, almost before knowing it, in accumulating a fortune, and achieving a reputation, which, to-day, is of itself worth half-a-dozen fortunes more.”12The author confirms that two years prior, Pfaff retired and sold his restaurant at 653 Broadway, “a much finer one than he commenced with, but still a basement,” leaving his business in the hands of “parties who, not having his tact, so reduced the custom, that the place finally reverted back to him again.”13

In this light, it seems that Clapp was right when he wrote about the modifications with regard to Pfaff’s clientele, including the statement that some former customers were no longer welcome in Cruyt’s. Even the renovations that Cruyt made to the place could not compensate for a seeming lack of customer service skills. One also has to wonder if Cruyt was as generous in allowing customers to run up tabs, as Pfaff was known to have been. As a result of the new owner’s rules and practices, however, “Cruyt’s” fast became “Pfaff’s” again, and by the time this story explaining the incident appeared, Pfaff had returned to the restaurant, and was, “conducting it on the original plan, doing better than ever.”14