The American Bohemians at Pfaff’s

The persons in the illustration may represent any of the American Bohemian crowd or, even Charles Pfaff himself since he often interacted with his customers.

At Pfaff’s, the American Bohemians would place their orders and “argue upon the light topics of the day, more particularly those with dramatic subjects which were at the time uppermost.” They were also known to debate “politics, literature, the arts

When the American Bohemians were not dashing off dramatic critiques or other articles to sell immediately to the newspapers, they held writing workshops at the cellar to aid one another in their other literary endeavors. In effect, they formed what has been referred to as “the first trade union of intellect.” Every man would bring “a new poem, editorial, or idea for a magazine sketch” to these occasions.17 The women of the coterie may or may not have joined the men in this particular activity; however, it is certainly possible that the female Bohemians were present at least as a part of the audience when new pieces were composed or shared. As early as 1860, The Chicago Press and Tribune suggested that the women writers and actresses who joined the American Bohemian crowd at Pfaff’s were as boisterous and witty as the men in Clapp’s circle. Writing for the

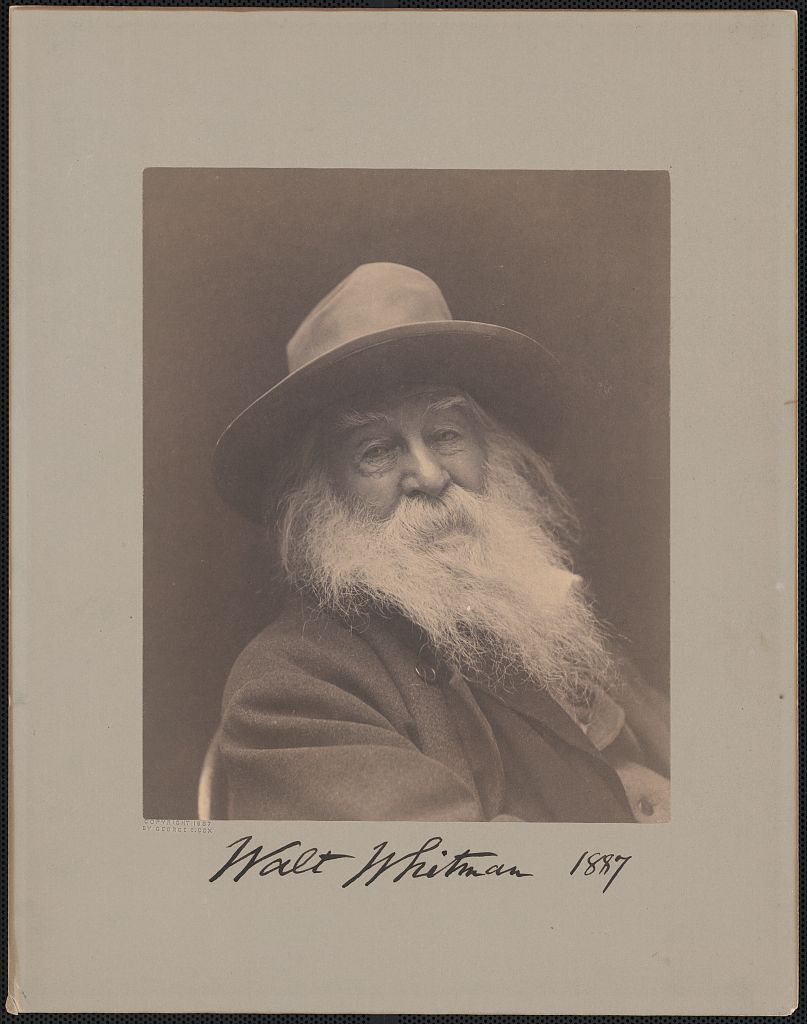

Approximately twice per week, the poet Walt Whitman took part in the aforementioned workshops by bringing rough drafts of his poems to share with the group. He would arrive at the beer cellar, hang his jerkin on a nail, and sit down, with a recent poem, or what he referred to as a new “barbaric yawp” written on a piece of paper that he had tucked carefully into his pocket—a pocket that he always felt contained “a great surprise” for his American Bohemian audience.20 After dinner, which at Pfaff’s “was always as good as one at Delmonico’s”—a reputable, higher-end drinking and eating establishment—Whitman would present his “half written ‘yawp’” or short poem to the Bohemians.21 Henry Clapp, Jr., encouraged the poet to read his work aloud by urging, “'Come, Whitman, you savage, open a page of nature for us.’”22 At least two accounts of Whitman’s participation in the Pfaffians’ versions of writing workshops and poetry readings suggest that the poet often talked about himself and his work “oh, so earnestly and well!”23 Some of the American Bohemians, especially Clapp, developed a fascination with Whitman’s unconventional poetic style. After all, if, as the New York Times put it in 1858, “the true Bohemian has either written an unsuccessful play, or painted an unsalable picture, or published an unreadable book, or composed an unsung opera, then the other Bohemians would have understood and, perhaps even sympathized both with Whitman’s disappointment in the sales for the first two editions of Leaves of Grass and in his attempts to find a publisher for the third volume.24

Because many of the literary Bohemians frequently wrote against conventional themes or established forms, most were talented if struggling writers much like Whitman himself. But they were often unable to find permanent employment, and, therefore, depended upon “poorly compensated chancework” and “precarious contributions to the story papers” for their livelihood.25 The articles, reviews, and poems that they composed at Pfaff’s or presented to their peers there were a source of income that these writers depended on in order to pay their rent and to repay Pfaff for the credit he so generously extended. To that end, the American Bohemians were contributors not just to the New-York Saturday Press—which could offer them little compensation for their work—but also to many other newspapers and magazines that were part of the burgeoning periodical culture of the mid-nineteenth century United States. A writer whom the Saturday Press identified only as “M” explained that each day a true literary Bohemian could be seen “flitting amongst the various newspaper offices: “Now he has an article for the Daily Wailer, and now a story for the Weekly Mummy, and again a sketch for the Family Gossip.”26 This emphasis on periodical writing is what led one Pfaffian to conclude that because many of the literary Bohemians at Pfaff’s had published pieces in Vanity Fair, the New York Leader, and Harper’s, “these men really controlled the periodical press and public opinion” in antebellum New York even though they met in a beer cellar.27

The fact that the American Bohemians wrote articles, composed poems, and read aloud to one another at Pfaff’s not only drew customers who wanted to watch the proceedings, but also ensured that Pfaff’s was associated with increased literary production. A few months after Pfaff’s opened at 647 Broadway, a writer from the New- York Traveler; and United States Hotel Directory praised the cellar, noting “The choice spirits meet here; and the artist, poet or litterateur, who has not drunk and eaten at Pfaff’s, knows not the most infallible source of inspiration nor the best cheer of life. Go to Pfaff’s!”28 The writer’s reference to the meeting of “choice spirits” at Pfaff’s refers to both the proprietor’s well-known stores of quality wine and beer as well as the exceptionally talented American Bohemian writers and artists that collaborate on their literary and dramatic productions in the cellar. He or she asserts that other writers and artists should come to Pfaff’s if they are in need of encouragement or motivation, while also implying that the most dependable sources of it are the menu and the atmosphere at Pfaff’s itself. There can be no doubt that these claims are intended to serve as an advertisement for the beer cellar because the writer ends with the phrase “Go to Pfaff’s!” These three words became a kind of advertising slogan for the beer cellar, and they accompanied advertisements in the New-York Saturday Press throughout 1859 and 1860. In fact, one of the very advertisements that includes the phrase—seemingly the ad from the Saturday Press that champions Pfaff’s Havana Cigars and international newspapers— also appears in the New-York Traveler, on the same page as the aforementioned short piece in which the writer insists that the cellar inspires the American Bohemians’ creative pursuits.It is not surprising then that Pfaff came to value his American Bohemian customers and advertisers so much that he often “kept his cellar open into the dawn for the sake of a handful of Bohemians engaged in a verse-making contest.”29 Even so, Pfaff had a rule that the closing time for his cellar should be one in the morning. He “frequently, though mildly endeavored” to enforce this policy, but the American Bohemians quickly discovered that they could talk him out of calling it a night so early:

Upon these occasions, which became rarer and rarer, it generally occurred that it required about one hour to get the proprietor into a proper frame of mind to humbly apologize for having dared to suggest that he wished to close his doors upon the Princes of Bohemia, and when this amend had been made it was Pfaff himself who was most reluctant to end the proceedings.30Once the American Bohemians had convinced Pfaff to allow his establishment to remain open and/or even perhaps to join their conversations and activities, they knew at this point that they could stay for as long as they liked. According to Louis Megargee’s 1890 Philadelphia Inquirer article that detailed some “Reminiscences of Bohemia Revived by the Death of Pfaff,” when the American Bohemians sat in Pfaff’s vault “[w]ith Pfaff’s beer and Pfaff’s pipes and tobacco and Pfaff’s rarebits” as well as their own preoccupation with “wit and humor and poetry and prose, time passed so quickly at the round table in the cellar alcove that all too frequently the sun rose upon the close of the session.”31 At last, Pfaff was able to shut down the saloon in the early morning hours and rest after a long workday, during which he had served the American Bohemians at least twice; once for dinner before they went out to the play or the opera and again when the performance was over. By the time Pfaff closed in the early hours of the morning, he had, at least on some occasions, been hosting this particular group some eight to ten hours since their arrival at dinner the previous evening with only a brief respite from their company between the end of the evening meal and the close of the show the Bohemians had chosen to see that night.

This page has paths:

- “GO TO PFAFF’S!” Audrey Clancy