Pfaff and the Restaurant in the 1870s

Another important event for the Pfaff family that occurred in the early 1870s was that Charles Pfaff, Jr., then approximately thirteen years of age, was sent away from his father’s beer cellar and from New York to continue his education. Charles Pfaff, Jr., entered a Moravian School known as

At the same time, the early 1870s saw the emergence of new, creative advertising strategies for Pfaff’s restaurant. One such advertisement that appeared in The American Enterprise in January 1872 was written in the form of a poem, entitled “  RHYMES AT A RESTAURANT.”8 The poem has a subtitle, printed in italics, that provides the name and address of the “Restaurant” in question: “C. Pfaff’s, 653 Broadway, New York.” Although certainly humorous in tone, the poem also functioned as a menu that gave potential customers insight into the foods and beverages available at Pfaff’s. The poet draws attention to Pfaff’s tea and his rhein wine and to the lager beer and coffee that helped make Pfaff famous since those are among the items that the American Bohemians had praised at 647 Broadway more than a decade earlier. Here, the poet also chooses to point out primarily the meats or the “beef,” the “Schinken” (ham), and the “mutton” that likely make up the main dinner courses at the cellar. There may even be a reference to the American Bohemians in the second line of the poem since Pfaff’s customers are designated as “Herr, Ritter, and Graf,” which can be translated from the German as “Man, Knights, and Count.” The American Bohemians were sometimes referred to as the “Knights of the Round Table,” and this word choice may suggest that the remaining members of the group are responsible for or at least associated with the creation of this poem.

RHYMES AT A RESTAURANT.”8 The poem has a subtitle, printed in italics, that provides the name and address of the “Restaurant” in question: “C. Pfaff’s, 653 Broadway, New York.” Although certainly humorous in tone, the poem also functioned as a menu that gave potential customers insight into the foods and beverages available at Pfaff’s. The poet draws attention to Pfaff’s tea and his rhein wine and to the lager beer and coffee that helped make Pfaff famous since those are among the items that the American Bohemians had praised at 647 Broadway more than a decade earlier. Here, the poet also chooses to point out primarily the meats or the “beef,” the “Schinken” (ham), and the “mutton” that likely make up the main dinner courses at the cellar. There may even be a reference to the American Bohemians in the second line of the poem since Pfaff’s customers are designated as “Herr, Ritter, and Graf,” which can be translated from the German as “Man, Knights, and Count.” The American Bohemians were sometimes referred to as the “Knights of the Round Table,” and this word choice may suggest that the remaining members of the group are responsible for or at least associated with the creation of this poem.

Even though the poem could substitute for the restaurant’s menu, it is perhaps even more important for its language and its rhyme scheme. The poem makes use of words from German, French, and English, all of which are languages that Charles Pfaff was known to speak. The writer’s linguistic ability and affinity for word play suggests that the intended audience for such a poem would know the meaning and pronunciation of the words from at least one and, ideally, more of the three languages that appear in the piece. Thus Pfaff seemingly continues to market his restaurant to a French and/or German speaking clientele. In addition to switching languages throughout the poem, another of the writer’s impressive linguistic feats is that the word at the end of each line ends in “aff.” All of the lines, therefore, are intended to rhyme or nearly rhyme with one another. The repetition of the “aff” sound throughout the poem constantly reminds the reader of the name of the proprietor and of the restaurant itself. The name “Pfaff” also actually appears four times throughout the poem. The “C. Pfaff” at the end of the poem is both the name of the proprietor and an encouragement for readers to “See Pfaff” for dinner and drinks.

Another feature that might attract customers is the poem’s mention of the restaurant’s staff. Once again the staff is presented as a veritable brigade of “nimble- foot[ed]” men that “wait” insofar as they serve the customers and are “waiting” or remaining in the establishment in anticipation of more patrons arriving at “THE RESTAURANT PFAFF.” Because these words are printed in capital letters, the reader’s eye is immediately drawn to the end of the poem and, of course, to the name of the restaurant. Even the title “Rhymes at a Restaurant” could be meant to suggest that this poem was composed at Pfaff’s cellar. Readers, therefore, not only imagine a group of patrons around a table writing these lines in the cellar, but they also learn that they can go and see for themselves the location the poet praises and, perhaps, even the very site where this combination of literature and advertising was created.

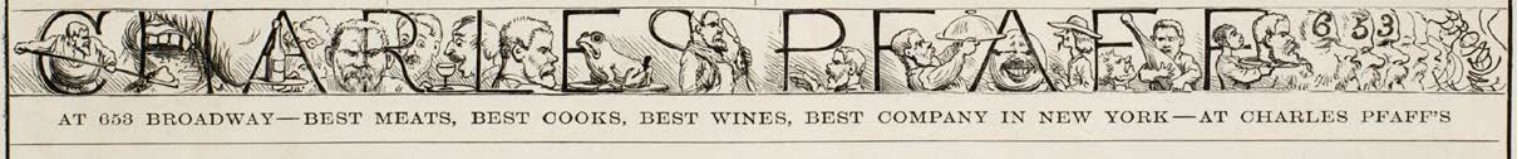

On the same page as the poem, another particularly unique ad for Pfaff’s appears, containing the words “CHARLES PFAFF” in capital letters (see Figure 10, Appendix A).9 Above, below, and between the letters of Pfaff’s name, the advertisement is illustrated with small comical sketches of Pfaff’s customers and possibly even Pfaff himself. Given that some of the American Bohemian group were also artists and illustrators, it is hard not to speculate that the advertisement may have been designed by one of the former members of Clapp’s crowd. In the far left, surrounded by the “C” that begins “CHARLES,” is an image of a large, stocky man with a beard shoveling food into a huge mouth, that appears where one would expect an oven to be depicted. This man may be Charles Pfaff since the illustration seems to match physical descriptions of the bar-owner.

If this is the case, then Pfaff appears several times throughout the ad performing tasks ranging from cooking to serving drinks in glasses and from holding a ladle for soup to staggering under the weight of a bottle of wine that seems to be as big as Pfaff himself. When he serves the drinks, he holds a wine glass on a tray so close to the head of one male customer that it seems he is literally playing “Ganymede” insofar as he seems to offer the cups so that the patrons could drink from them while he continues to hold them in place. On the far right—in what is perhaps the strangest and most graphic illustration of the advertisement—Pfaff’s own head, having been separated from the rest of his body, is offered up to the reader on a platter carried by a servant or a waiter. Pfaff’s head, particularly the lines of his face, gradually become through a series of slightly altered or morphing portraits the name of the street where Pfaff’s is located. At the end of the advertisement, therefore, Pfaff’s face has become the word “BROADWAY,” which curls around the last remaining lines of Pfaff’s head. This suggests that Pfaff and his restaurant are synonymous with the famous New York Street since this is at least his third restaurant on Broadway. Pfaff’s head on the platter may symbolize the bar-owner’s sacrifice, that is, his efforts to satisfy his customers by managing each aspect of the business himself. It was this hard work and determination that Pfaff had been praised for years earlier when he again stepped into the position of owner following the unsuccessful changes Cruyt made in his business model. In short, what patrons get at Pfaff’s and, indeed, the reason why they go to the restaurant is Pfaff himself and his impeccable customer service.

One of the most noteworthy and humorous illustrations that accompany the advertisement shows Pfaff carrying a large, living frog around the restaurant on a platter as if to serve the animal to a guest or to drop it into a cooking pot. The frog stares gloomily back at Pfaff as if it knows and, with good reason, dreads its fate. The frog may be a reference to the restaurant’s menu,